In this panel of maps the relationship between the district of Parbhani (in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra) and water is graphically depicted over time. The blue squares are water bodies, as seen by a satellite equipped to do so. The intensity of the blue colour denotes how much water is standing in that coloured square by volume – the deeper the blue, the more the water.

Water bodies consist of all surface water bodies and these are: reservoirs, irrigation tanks, lakes, ponds, and rivers or streams. There will be variation in the spatial dimensions of these water bodies depending on how much rainfall the district has recorded, and how the collected water has been used during the season and year. In addition to these surface water bodies, there are other areas representing water surface that may appear, such as due to flood inundations, depressions in flood plains, standing water in rice crop areas during transplantation stages. Other than medium and large reservoirs, these water features are treated as seasonal and some may exist for only a few weeks.

The importance of monitoring water collection and use at this scale can be illustrated through a very brief outline of Parbhani. The district has 830 inhabited villages distributed through nine tehsils that together occupy 6,214 square kilometres, eight towns, 359,784 households in which a population of 1.83 million live (1.26 rural and 0.56 million urban). This population includes 317,000 agricultural labourers and 295,000 cultivators – thus water use and rainfall is of very great importance for this district, and indeed for the many like it all over India.

This water bodies map for Parbhani district is composed of 18 panels that are identical spatially – that is, centred on the district – and display the chronological progression of water accumulation or withdrawal. Each panel is a 15-day period, and the series of mapped fortnights begins on 1 January 2015.

The panels tell us that there are periods before the typical monsoon season (1 June to 30 September) when the accumulation of water in surface water bodies has been more than those 15-day periods found during the monsoon season. See in particular the first and second fortnights of March, and the first fortnight of April.

During the monsoon months, it is only the two fortnights of June in which the accumulation of water in the surface water bodies of Parbhani district can be seen. The first half of July and the second half of August in particular have been recorded as relatively dry.

This small demonstration of the value of such information, provided at no cost and placed in the public domain, is based on the programme ‘Satellite derived Information on Water Bodies Area (WBA) and Water Bodies Fraction (WBF)’ which is provided by the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), Department of Space, Government of India.

For any of our districts, such continuous monitoring is an invaluable aid to: facilitate the study of water surface dynamics in river basins and watersheds; analyse the relationships between regional rainfall scenarios and the collection and utilisation of water in major, medium reservoirs and irrigation tanks and ponds; inventory, map and administer the use of surface water area at frequent intervals, especially during the crop calendar applicable to district and agro-ecological zones.

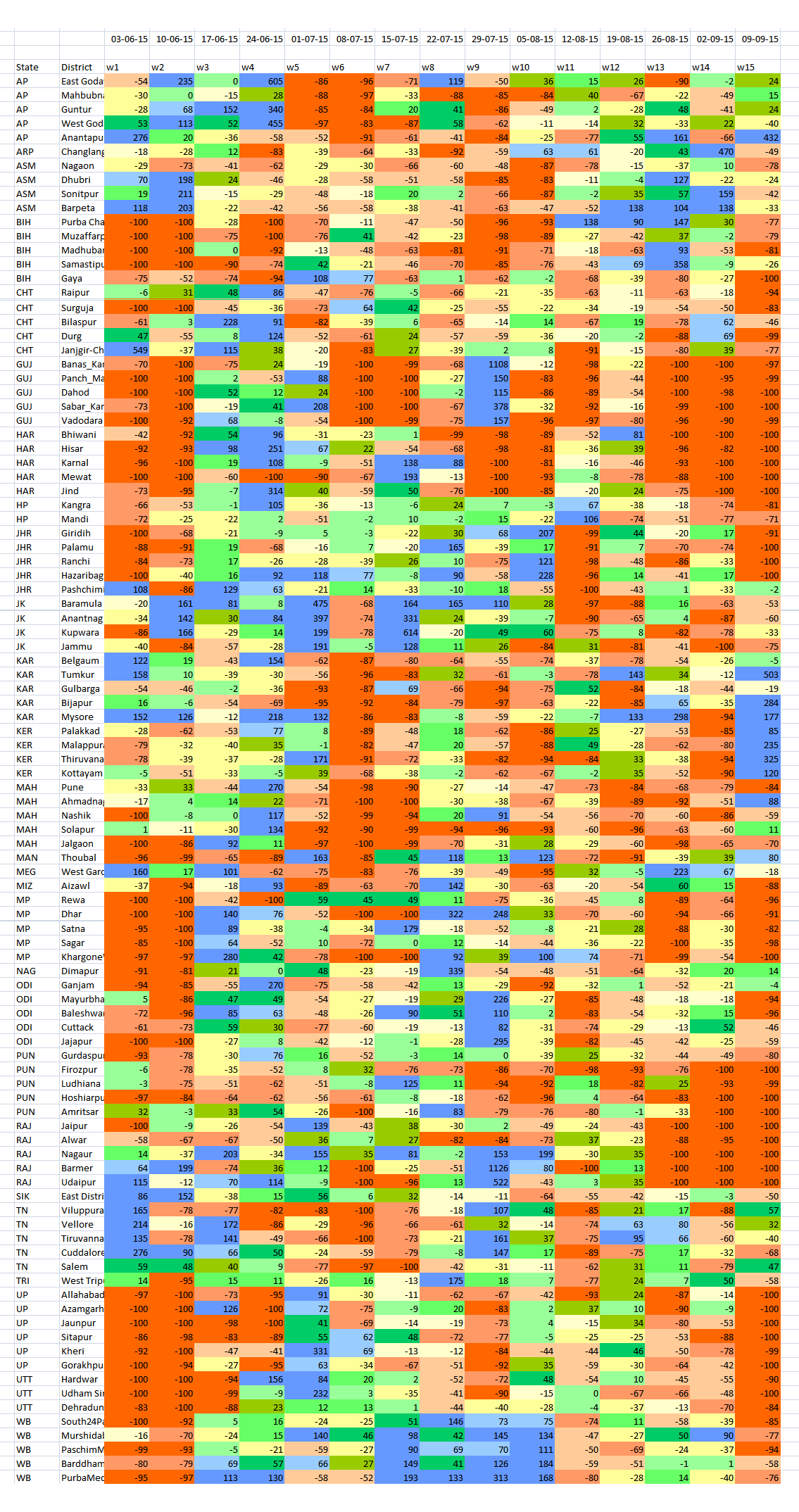

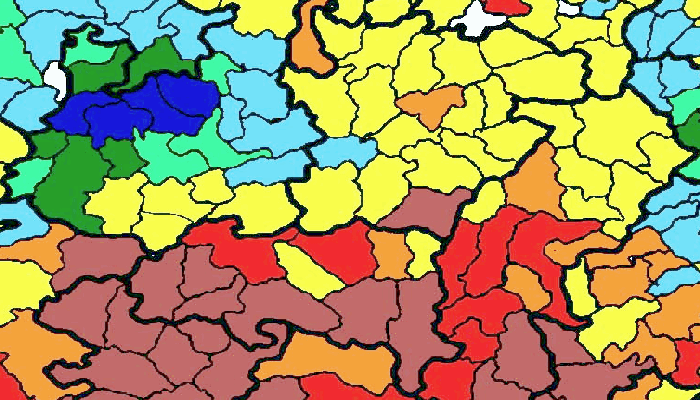

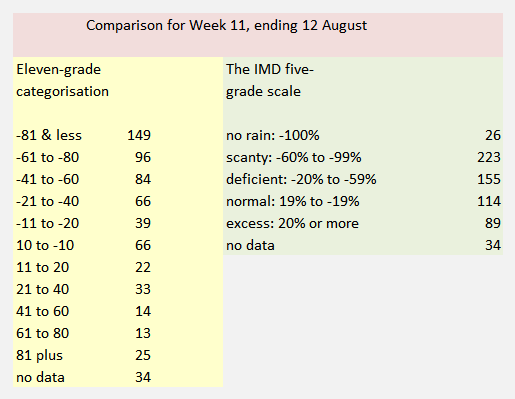

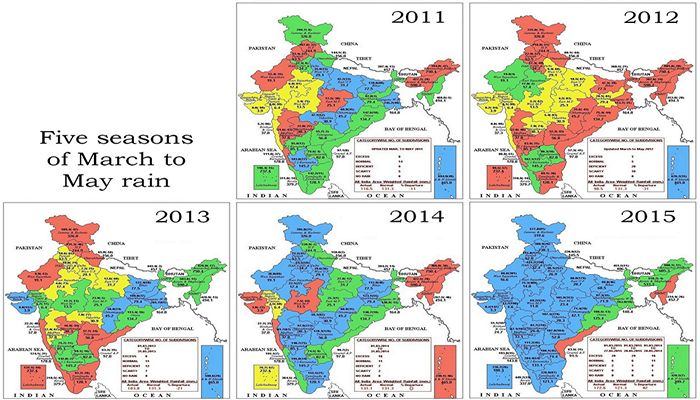

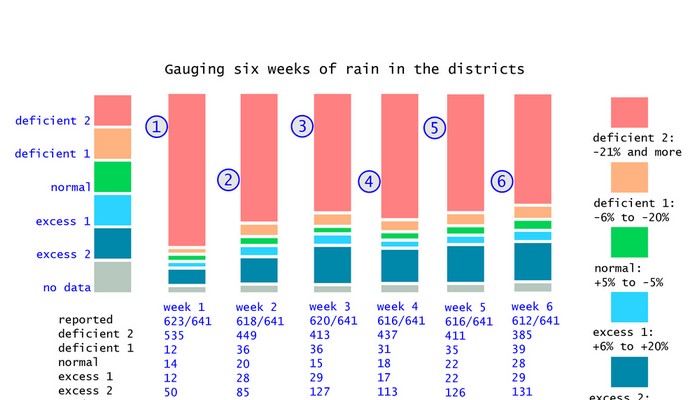

From the first week of June 2014 until the middle of September 2014, there have been floods and conditions equivalent to drought in many districts, and for India the tale of monsoon 2014 comes from a reading of individual districts, not from a national ‘average’ or a ‘cumulative’. [

From the first week of June 2014 until the middle of September 2014, there have been floods and conditions equivalent to drought in many districts, and for India the tale of monsoon 2014 comes from a reading of individual districts, not from a national ‘average’ or a ‘cumulative’. [

We urge the Ministry of Earth Sciences, the India Meteorology Department and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to cease the use of a ‘national’ rainfall average to describe the progress of monsoon 2014. This is a measure that has no meaning for cultivators in any of our agro-ecological zones, and has no meaning for any individual taluka or tehsil in the 36 meteorological sub-divisions. What we need to see urgently adopted is a realistic overview that numerically and graphically explains the situation, at as granular a level as possible.

We urge the Ministry of Earth Sciences, the India Meteorology Department and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to cease the use of a ‘national’ rainfall average to describe the progress of monsoon 2014. This is a measure that has no meaning for cultivators in any of our agro-ecological zones, and has no meaning for any individual taluka or tehsil in the 36 meteorological sub-divisions. What we need to see urgently adopted is a realistic overview that numerically and graphically explains the situation, at as granular a level as possible.