Prime Minister Narendra Modi employed an event from the life of Sri Adi Shankarachaya, the late 8th century spiritual master, to emphasise the importance of dialogue in finding ways to deal with climate change and also problems that are international in scope, such as conflict and the need for environmental consciousness.

Modi said this at the inauguration in New Delhi of ‘Samvad’, the Global Hindu-Buddhist Initiative on Conflict Avoidance and Environment Consciousness. Amongst those who listened to his address were: the Most Venerable Sayadaw Dr Asin Nyanissara, Founder Chancellor of the Sitagu International Buddhist Academy in Myanmar; Her Excellency Mrs Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, the former President of Sri Lanka; Minoru Kiuchi, State Minister for Foreign Affairs of Japan; and Sri Sri Ravi Shankar.

The Prime Minister said that the themes chosen for the symposium – avoiding conflicts, moving towards environmental consciousness and free and frank dialogue – “may appear independent but they are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are mutually dependent and supportive”. Calling climate change a pressing global challenge, the PM said a response to climate change calls for collective human action.

“The Buddhist tradition, in all of its historical and cultural manifestations, encourages greater identification with the natural world because from a Buddhist perspective nothing has a separate existence,” he said. “The impurities in the environment affect the mind, and the impurities of mind also pollute the environment. In order to purify the environment, we have to purify the mind.”

He pointed out that ethical values of personal restraint in consumption and environmental consciousness are deeply rooted in Asian philosophical traditions, especially in Hinduism and Buddhism which along with other faiths such as Confucianism, Taoism and Shintoism have undertaken greater responsibility to protect the environment. “Hinduism and Buddhism with their well-defined treatises on Mother Earth can help examine the changes in approach that need to be made.”

Modi said that the present generation has the responsibility of holding in trust the rich natural wealth for future generations. “The issue is not merely about climate change; it is about climate justice,” he said. He spoke of the need to shift from an ideological approach to a philosophic one. “The essence of philosophy is that it is not a closed thought, while ideology is a closed one. So philosophy not only allows dialogue but it is a perpetual search for truth through dialogue.”

Advocating dialogue which produces no anger or retribution, Modi said that one of the greatest examples of such dialogue was the one between Adi Sankaracharya and Mandana Mishra, a debate whose significance has educated and edified many generations of Indians. The PM related that Adi Sankaracharya wanted to establish through dialogue and debate with the highest authority on ritualism that rituals were not necessary for attaining ‘mukti’, whereas Mandana Mishra wanted to prove that Sankara was wrong in dismissing rituals.

“This was how, in ancient India, debates on sensitive issues between scholars avoided such issues being settled in streets. Adi Sankara and Mandana Mishra held a debate and Sankara won. But the more important point is not the debate itself but how was the debate was conducted. It is a fascinating story that will ever remain one of the highest forms of debate for all times for humanity,” he said.

This is unlikely to result in any constructive recognition of all that is linked. A country’s total emissions is one part of the ‘development’ picture and others are at least as important. There are also tons of CO2 emitted per capita (India has often said that its per capita emissions are far below those of the West). And there is per capita consumption of electricity (which is still mainly generated by burning coal).

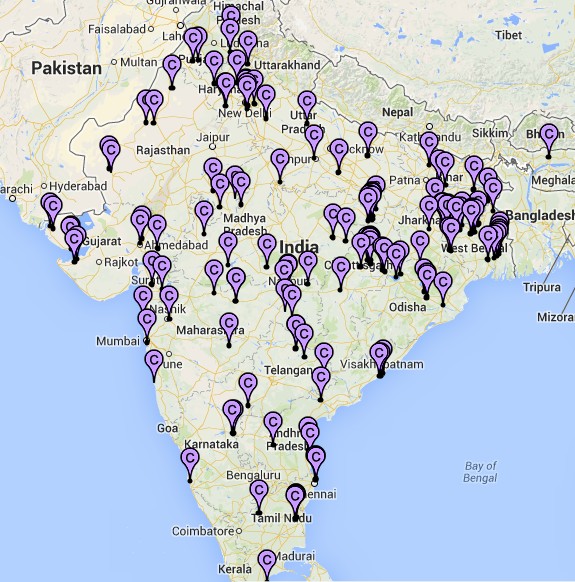

This is unlikely to result in any constructive recognition of all that is linked. A country’s total emissions is one part of the ‘development’ picture and others are at least as important. There are also tons of CO2 emitted per capita (India has often said that its per capita emissions are far below those of the West). And there is per capita consumption of electricity (which is still mainly generated by burning coal). Thus the message to policy-makers is clear – what counts is what you do at home, in states and districts. The expectation that “international cooperation” should guide effective adaptation at all levels is no longer (and in our view has never been) tenable.

Thus the message to policy-makers is clear – what counts is what you do at home, in states and districts. The expectation that “international cooperation” should guide effective adaptation at all levels is no longer (and in our view has never been) tenable.

We must question the profligacy that the Goyal team is advancing in the name of round the clock, reliable and affordable electricity to all. To do so is akin to electoral promises that are populist in nature – and which appeal to the desire in rural and urban residents alike for better living conditions – and which are entirely blind to the environmental, health, financial and behavioural aspects attached to going ahead with such actions. In less than a fortnight, prime minister Narendra Modi (accompanied by a few others)

We must question the profligacy that the Goyal team is advancing in the name of round the clock, reliable and affordable electricity to all. To do so is akin to electoral promises that are populist in nature – and which appeal to the desire in rural and urban residents alike for better living conditions – and which are entirely blind to the environmental, health, financial and behavioural aspects attached to going ahead with such actions. In less than a fortnight, prime minister Narendra Modi (accompanied by a few others)