A village threatened by rising floodwaters in Arunachal Pradesh. Image: Arunachal Times

Torrential rain in north-east India has caused rivers to swell with water, several above their danger marks, and has isolated entire districts. Reports from Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya – states that have experienced heavy to very heavy rain over the last four days – indicate a situation for the region that is approaching an emergency.

#monsoon2015 Next 6 days' rain for NE India. Red hues are 50-90 mm/day. Intensity lessens from 15th #Assam #Arunachal pic.twitter.com/YWEJ2BQCFD

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) June 10, 2015

The Indian Express has reported that thousands of people in Assam have been affected with several rivers, including the Brahmaputra, overflowing their banks. The rivers have breached embankments, inundated villages and damaged standing crops, affecting over 80,000 people, according to the state disaster management body.

The Arunachal Times has reported that the districts of Upper Siang, Dibang Valley and Anjaw are cut off from the region due to torrential rainfall which has triggered flash floods and landslides at various locations. Major rivers in Arunachal Pradesh including the Siang are in spate. The Echo of Arunachal has reported that Pasighat, the state’s oldest administrative town, is under threat of inundation and the provision of water and electricity to town inhabitants has stopped.

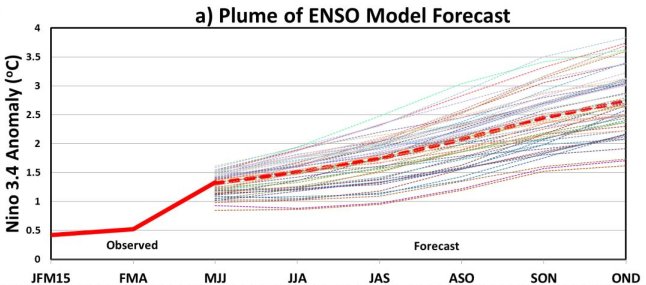

Whether the monsoon starts off on time, whether the June, July, August and September rainfall averages are met, and whether the seasonal pattern of the monsoon is maintained are expectations that must now be set aside.

Whether the monsoon starts off on time, whether the June, July, August and September rainfall averages are met, and whether the seasonal pattern of the monsoon is maintained are expectations that must now be set aside.

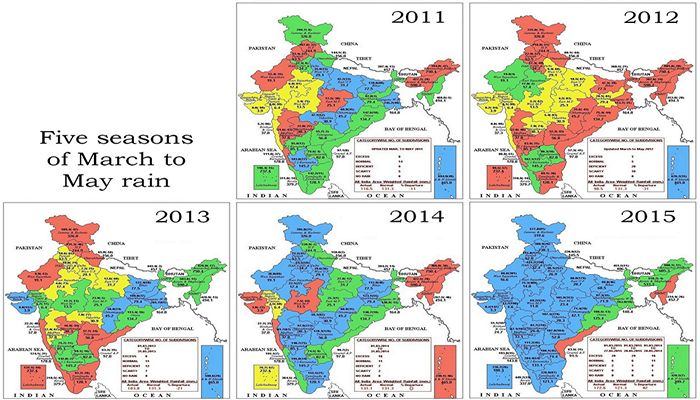

Our coverage of the ‘mausam’, the Indian summer monsoon of 2015, has begun. The unseasonal rains of March and April, which have proved so destructive to farmers, have shown why the conventional monsoon season must be widened. You will find all

Our coverage of the ‘mausam’, the Indian summer monsoon of 2015, has begun. The unseasonal rains of March and April, which have proved so destructive to farmers, have shown why the conventional monsoon season must be widened. You will find all

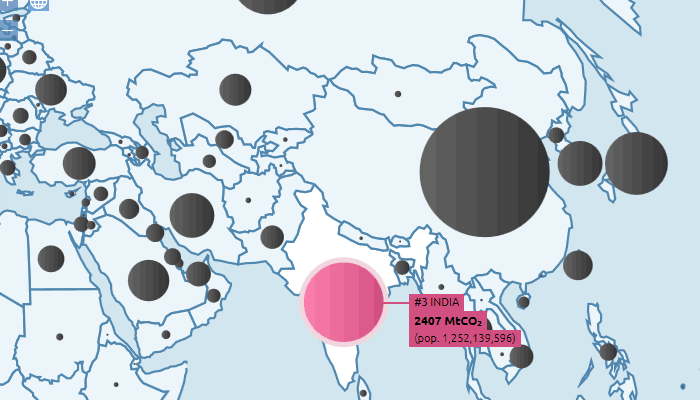

This is unlikely to result in any constructive recognition of all that is linked. A country’s total emissions is one part of the ‘development’ picture and others are at least as important. There are also tons of CO2 emitted per capita (India has often said that its per capita emissions are far below those of the West). And there is per capita consumption of electricity (which is still mainly generated by burning coal).

This is unlikely to result in any constructive recognition of all that is linked. A country’s total emissions is one part of the ‘development’ picture and others are at least as important. There are also tons of CO2 emitted per capita (India has often said that its per capita emissions are far below those of the West). And there is per capita consumption of electricity (which is still mainly generated by burning coal). Thus the message to policy-makers is clear – what counts is what you do at home, in states and districts. The expectation that “international cooperation” should guide effective adaptation at all levels is no longer (and in our view has never been) tenable.

Thus the message to policy-makers is clear – what counts is what you do at home, in states and districts. The expectation that “international cooperation” should guide effective adaptation at all levels is no longer (and in our view has never been) tenable.

I have taken the data from two sources. One is the Census of India, for the census years 2011, 2001 and 1991. The other is the Road Transport Yearbook (2011-12) issued by the Transport Research Wing, Ministry Of Road Transport and Highways, Government Of India. The yearbook includes a table with the total number of registered vehicles (in different categories of vehicle – two-wheelers, cars, buses, goods vehicles, others) for every year. The number of households is from the census years, with simple decadal growth applied annually between census years. I have not yet found the detailed data that will let me refine this finding between urban and rural populations.

I have taken the data from two sources. One is the Census of India, for the census years 2011, 2001 and 1991. The other is the Road Transport Yearbook (2011-12) issued by the Transport Research Wing, Ministry Of Road Transport and Highways, Government Of India. The yearbook includes a table with the total number of registered vehicles (in different categories of vehicle – two-wheelers, cars, buses, goods vehicles, others) for every year. The number of households is from the census years, with simple decadal growth applied annually between census years. I have not yet found the detailed data that will let me refine this finding between urban and rural populations. The implications are several and almost all of them are an alarm signal. Especially for urban areas – where most of the buying of vehicles for households has taken place – the physical space available for the movement of people and goods has increased only marginally, but the number of motorised contrivances (cars, motor-cycles, scooters and more recently stupidly large SUVs and stupidly large and expensive luxury cars) has increased quickly. Naturally this ‘growth’ of wheeled metal has choked our city wards.

The implications are several and almost all of them are an alarm signal. Especially for urban areas – where most of the buying of vehicles for households has taken place – the physical space available for the movement of people and goods has increased only marginally, but the number of motorised contrivances (cars, motor-cycles, scooters and more recently stupidly large SUVs and stupidly large and expensive luxury cars) has increased quickly. Naturally this ‘growth’ of wheeled metal has choked our city wards. More motorised conveyance per household also means more fuel demanded per household, and more fuel (and money) wasted because households are taught (by the auto industry with the encouragement of the foolish cohorts I mentioned earlier) that they are entitled to wasteful personal mobility. Over 20 years, the number of cars per household has increased 4.1 times but the number of buses per household has increased only 2.8 times. That is embarrassing proof of our un-ecological and climate unfriendly new habits.

More motorised conveyance per household also means more fuel demanded per household, and more fuel (and money) wasted because households are taught (by the auto industry with the encouragement of the foolish cohorts I mentioned earlier) that they are entitled to wasteful personal mobility. Over 20 years, the number of cars per household has increased 4.1 times but the number of buses per household has increased only 2.8 times. That is embarrassing proof of our un-ecological and climate unfriendly new habits.