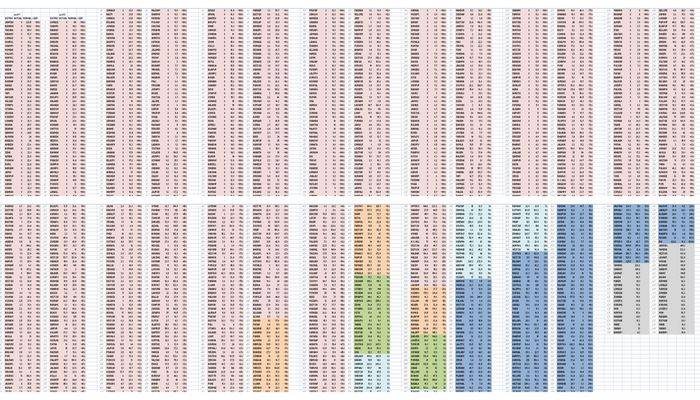

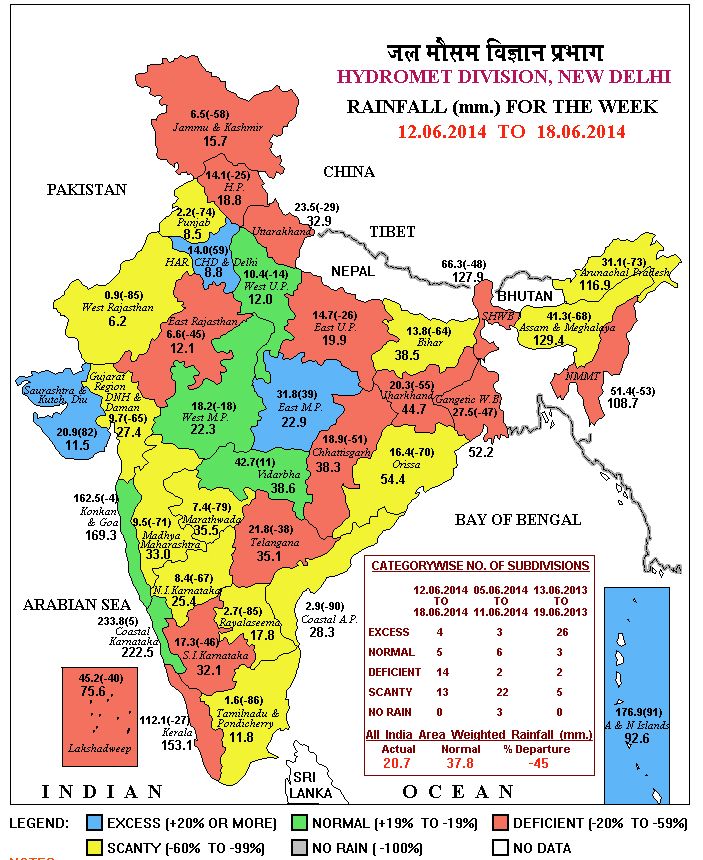

We now have rain data for four complete weeks from the India Meteorological Department (IMD) and for all the districts that have reported the progress of the monsoon. The overall picture is even more serious than reported earlier because of the falling levels of water in the country’s major reservoirs. [05 to 11 June is the first week. 12 to 18 June is the second week. 19 to 25 June is the third week. 26 June to 02 July is the fourth week.]

Using the new measure of assessing the adequacy of district rainfall (and not the meteorological gradations that is the IMD standard), in the fourth week of the monsoon the number of districts that reported normal rains in that week (+5% to -5%) is 16; deficient 1 (-6% to -20%) is 31; deficient 2 (-21% and more) is 437; excess 1 (+6% to +20%) is 17; excess 2 (+21% and more) is 113; no data was reported from 25.