Insat-3D’s view of the path inland of Hudhud at 1730 IST (5:30pm IST) on 12 October. The cyclonic storm is now moving north-northwest through Odisha into Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and south Bihar. Image: IMD

Oct 14 – The Armed Forces have further stepped up their rescue and relief operations in the coastal areas of Andhra Pradesh and Odisha. The Press Information Bureau has reported that eight ‘composite’ Army teams have been deployed in Vishakhapatnam and another eight teams in Srikakulam.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Andhra Pradesh chief minister N Chandrababu Naidu examining pictures of destruction caused by Cyclone HudHud, at Vizag Collectorate, on 14 October 2014. Image: PIB

The Indian Air Force has deployed C-17, C130J, AN-32, IL-76, Mi-17 and Chetak aircraft and helicopters for rescue and relief work. A total of 120 tonnes of essential supplies have been airlifted to Visakhapatnam from Vijayawada and Rajamundry, while essential supplies have also been marshalled at the Naval airfield at Visakhapatnam. Until the evening of 14 October, 36 sorties were made towards relief operations. Two road clearance teams of Army have been employed in the north of Srikakulum district and the road between Achutapuram and Vizag has been cleared by the armed forces teams.

An aerial survey was conducted by C-130J of the IAF and P-8I of the Navy with satellite imagery having been used to assess the impact of cyclone Hudhud while coastal reconnaissance is being done by the Coast Guard. Additional Engineer Units of the Army are being flown to Visakhapatnam.

Oct 12 – The IMD has issued its evening alert on cyclone Hudhud. The 1700 IST (5:00pm IST) alert contains a heavy rainfall warning and a wind warning.

Heavy rainfall warning: Rainfall at most places with heavy (6.5-12.4 cm) to very heavy falls (12.5-24.4 cm) at a few places and isolated extremely heavy falls (>24.5 cm) would occur over West and East Godavari, Visakhapatnam, Vijayanagaram and Srikakulam districts of north Andhra Pradesh and Ganjam, Gajapati, Koraput, Rayagada, Nabarangpur, Malkangiri, Kalahandi, Phulbani districts of south Odisha during next 24 hrs. Rainfall would occur at most places with heavy to very heavy rainfall at isolated places over Krishna, Guntur and Prakasham districts of Andhra Pradesh and north Odisha during the same period. Rainfall at most places with heavy falls at a few places would occur over south Chattisgarh, adjoining Telangana and isolated heavy to very heavy falls over north Chattisgarh, east Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand and Bihar.

Cyclone Hudhud will degrade into a severe cyclonic storm, then a cyclonic storm and by 13 October morning into a deep depression. Until 14 October it will continue to pose a danger with heavy rainfall and high winds. This IMD table explains why.

Wind warning: Current gale wind speed reaching 130-140 kmph gusting to 150 kmph would decrease gradually to 100-110 kmph gusting to 120 kmph during next 3 hours and to 80-90 kmph during subsequent 6 hours over East Godavari, Visakhapatnam, Vizianagaram and Srikakulam districts of North Andhra Pradesh. Wind speed of 80-90 kmph gusting to 100 kmph would prevail over Koraput, Malkangiri, Nabarangpur and Rayagada districts during next 6 hrs and 50 to 60 kmph during subsequent 12 hrs. Squally wind speed reaching upto 55-65 kmph gusting to 75 kmph would also prevail along and off West Godavari and Krishna districts of Andhra Pradesh, Ganjam and Gajapati districts of Odisha, south Chattisgarh and adjoining districts of north Telangana during next 12 hours.

Odisha district control room phone numbers have been distributed thanks to eodisha.org.

They are: Mayurbhanj 06792 252759, Jajpur 06728 222648, Gajapati 06815 222943, Dhenkanal 06762 221376, Khurda 06755 220002, Keonjhar 06766 255437, Cuttack 0671 2507842, Ganjam 06811 263978, Puri 06752 223237, Kendrapara 06727 232803, Jagatsinghpur 06724 220368, Balasore 06782 26267, Bhadrak 06784 251881.

There are reports on twitter that the leading edge of cyclone Hudhud crossed the coast at around 1030 IST (0500 UTC). The reported maximum wind speed is just above 200 kmph which means the destructive force threatens structures too.

Strangely calm right Now. Everything outside is eerily quiet. We’re IN THE EYE of the storm now #Cyclone #Hudhud #Vizag #Visakhapatnam

— Deepa Ghosh (@deepaghosh2007) October 12, 2014

This tweet means the western ‘wall’ of the cyclone has now crossed completely – it has taken just under two hours. The eastern ‘wall’ crossing will now begin.

Cyclone #Hudhud hits the coast of Andhra Pradesh at Kailashgiri in Visakhapatnam. Live updates http://t.co/FQU6kZvVSR pic.twitter.com/YGzZYwIUpg

— Sudhan Rajagopal BJP (@BJPsudhanRSS) October 12, 2014

Cyclone #Hudhud makes landfall at Bheemunipatanam, slightly north of Vizag. #TVnews

— Saswat K Swain (@saswat28) October 12, 2014

Roofs of houses fly away like leaves, huge trees falling everywhere #Hudhud creating maximum destruction.

— Imran Baig (@imranbaig) October 12, 2014

Navy officials warn that there will be a lull in the storm at around 11.30 am, but the storm will again intensify after that for a few hours.

Zee News has a list of cancelled and curtailed trains.

At least 400,000 people have been evacuated from the coastal areas of Andhra Pradesh and Odisha states as authorities aimed for zero casualties.

Oct 11 -Where is Cyclone Hudhud and how fast is it moving towards land? The India Meteorological Department has said in its most recent alert – 1430/2:30pm on 11 October – that “the Very Severe Cyclonic Storm” is now about 260 kilometres south-east of Visakhapatnam and 350 km south-south-east of Gopalpur. IMD expects the cyclone to travel north-west and cross the coast of north Andhra Pradesh, near Visakhapatnam, by mid-morning on 12 October 2014.

The projected path of the cyclone and its outer rainbands, which in the case of Hudhud are around 80 km thick measured from the eye. Image: GDACS

Around 100,000 people have been evacuated in Andhra Pradesh to high-rise buildings, shelters and relief centres, with plans to move a total of 300,000 to safety. Authorities in Odisha said they were monitoring the situation and would, if necessary, move 300,000 people most at risk.

The evacuation effort was comparable in scale to the one that preceded Cyclone Phailin exactly a year ago, and which was credited with minimising the fatalities to 53. When a huge storm hit the same area 15 years ago, 10,000 people died.

Authorities have been stocking cyclone shelters with dry rations, water purification tablets and generators. They have opened up 24-hour emergency control rooms and dispatched satellite phones to officials in charge of vulnerable districts.

IMD’s table of wind speeds at the surface (sea level) brought by Hudhud. Note the exceptionally strong winds between 2330/11:30pm on 11 October and 1130/11:30am on 12 October.

The AP government has cancelled leaves of employees and has asked everyone to remain on duty on the weekend. In Vizag, where the cyclone is expected to make landfall, the administration has opened 175 shelters and moved close to 40,000 people from the coastal villages. In Srikakulam, people of 250 villages in 11 mandals which may be affected have been evacuated.

Vishakhapatnam, Bhimunipatnam, Chittivalasa and Konada are expected to face storm surges of over 1 metre. Source: GDACS

While human casualties are not expected due to the massive evacuation, power and telecommunication lines will be uprooted leading to widespread disruption. A warning has been issued that flooding and uprooted trees will cut off escape routes, national and state highways and traffic is being regulated to ensure that no one is caught in the flash floods caused by heavy rains.

Officials said that National Disaster Response Force teams have been strategically placed along the coast to be deployed wherever they are required. Railways has cancelled all trains passing through the three districts which are likely to be affected.

The IMD has issued a “Heavy Rainfall Warning” which has said that driven by the cyclonic winds, rainfall at most places along the AP and Odisha coast will be heavy (6.5–12.4cm) to very heavy (12.5–24.4 cm). These places include West and East Godavari, Visakhapatnam, Vijayanagaram and Srikakulam districts of north Andhra Pradesh and Ganjam, Gajapati, Koraput, Rayagada, Nabarangpur, Malkangiri, Kalahandi, Phulbani districts of south Odisha.

This panel of four images shows the wind patterns of the cyclone at different altitudes. Top left is at 1,000 millibars (mb) of atmospheric pressure which is around sea level, top right is at 850 mb which is at around 1,500 metres high, bottom left is at 700 mb which is at around 3,500 metres, and bottom right is at 500 mb which is at around 5,000 metres. The direction of the greenish lines shows the winds rushing into the cyclonic centre. The visualisations have been collected from the ‘earth.nullschool.net’, which visually processes global weather conditions forecast by supercomputers and updated every three hours.

The India Meteorological Department said on the evening of 10 October that the “Very Severe Cyclonic Storm” is centered near latitude 15.0ºN and longitude 86.8ºE about 470 km east-southeast of Visakhapatnam and 520 km south-southeast of Gopalpur. This was the fix IMD had on the centre of the cyclone at 1430 IST on 10 October 2014.

Here are the salient points from news reports released during the afternoon of 10 October:

Cyclone Hudhud will cross the north Andhra Pradesh coast on October 12 and is expected to make landfall close to Visakhapatnam, according to the Cyclone Warning Centre (CWC) at Visakhapatnam. “It is forecast that Hudhud, which is already a severe cyclonic storm, will intensify into a very severe cyclonic storm in next 12 hours. Hudhud is likely to make landfall on October 12 close to Visakhapatnam,” said IMD’s Hyderabad centre.

Cyclone Hudhud has moved closer to the coast of Odisha and eight districts of the state are likely to be affected by it. The districts likely to be affected by the cyclone are Ganjam, Gajapati, Rayagada, Koraput, Malkangiri, Nabarangpur, Kalahandi and Kandhamal. All these districts have been provided with satellite phones for emergency and constant vigil was being maintained on the rivers like Bansadhara, Rusikulya and Nagabali as heavy rain is expected in southern districts.

With cyclone Hudhud fast approaching the states of Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh today spoke to the chief ministers of the three states on the steps being taken to deal with the situation. Odisha Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik sought satellite phones which could be used in case high-speed winds disturbed the telecommunication system.

According to the India Meteorological Department, the wind speeds of cyclone Hudhud will be less than what the east coast experienced during Phailin in October 2013. The wind speed during cyclone Phailin was nearly 210 kmph, which made the cyclone the second-strongest ever to hit India’s coastal region. The country had witnessed its severest cyclone in Odisha in 1999.

Frequent updates and advisories can also be found at GDACS – the Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System (a cooperation framework under the UN umbrella). GDACS provides real-time access to web-based disaster information systems and related coordination tools.

Cities that will directly be affected by cyclone Hudhud are Vishakhapatnam in Andhra Pradesh, Jagdalpur in Chhattisgarh, Vizianagaram in AP, Bhogapuram in AP, and Anakapalle in AP.

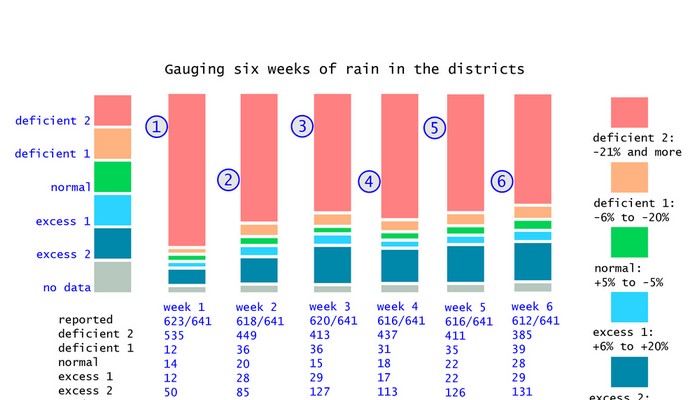

From the first week of June 2014 until the middle of September 2014, there have been floods and conditions equivalent to drought in many districts, and for India the tale of monsoon 2014 comes from a reading of individual districts, not from a national ‘average’ or a ‘cumulative’. [

From the first week of June 2014 until the middle of September 2014, there have been floods and conditions equivalent to drought in many districts, and for India the tale of monsoon 2014 comes from a reading of individual districts, not from a national ‘average’ or a ‘cumulative’. [

We urge the Ministry of Earth Sciences, the India Meteorology Department and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to cease the use of a ‘national’ rainfall average to describe the progress of monsoon 2014. This is a measure that has no meaning for cultivators in any of our agro-ecological zones, and has no meaning for any individual taluka or tehsil in the 36 meteorological sub-divisions. What we need to see urgently adopted is a realistic overview that numerically and graphically explains the situation, at as granular a level as possible.

We urge the Ministry of Earth Sciences, the India Meteorology Department and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to cease the use of a ‘national’ rainfall average to describe the progress of monsoon 2014. This is a measure that has no meaning for cultivators in any of our agro-ecological zones, and has no meaning for any individual taluka or tehsil in the 36 meteorological sub-divisions. What we need to see urgently adopted is a realistic overview that numerically and graphically explains the situation, at as granular a level as possible. Every week, the Central Water Commission releases to the public and to government departments the numbers that describe how much water is stored in 85 reservoirs in India. These are the reservoirs designated as nationally important, because of their roles in providing water for large irrigated command areas and for generating hydro-electric power (37 of these dams).

Every week, the Central Water Commission releases to the public and to government departments the numbers that describe how much water is stored in 85 reservoirs in India. These are the reservoirs designated as nationally important, because of their roles in providing water for large irrigated command areas and for generating hydro-electric power (37 of these dams).