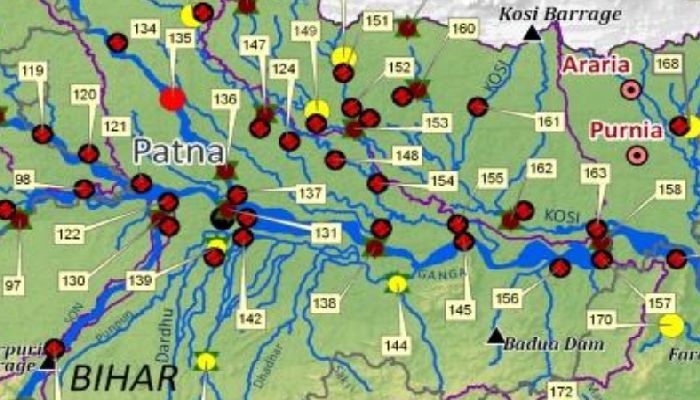

We find that the heavy rains that soaked the north Gujarat plains on the night of 1/2 July are testimony to the genius and far-sightedness of the builders of the Rani-ki-Vav, the famed stepwell which was initially built as a memorial to a king in the 11th century AD. The central heavy rainfall zone was immediately to the north-west of Patan, the town nearest to the Rani-ki-Vav, and it is precisely for this sort of rain that this fabulously constructed stepwell was built.

Rain for the Rani. At about 8pm on 1 July, dense rainclouds hung over the entire north #Gujarat plains, from ancient Dholavira to Dahod ..2

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

..by 8:30 pm showers were being reported from towns in the region while farther north in #Rajasthan, heavy rain pelted Barmer and Jalor ..3

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

..Rain for the Rani. At around 9pm the rainfall had become very heavy, reaching 15mm/hour, quickly leaching into the parched soil ..4 pic.twitter.com/zHLFHzcVmH

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

..The cores of two cloud masses were converging. The heavy rain was now on two parallel fronts each about 300 km wide ..5 pic.twitter.com/gamGJtCQGp

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

.. Rain for the Rani. At around midnight the Rajasthan and Gujarat core rainfall zones merged and the intensity lessened #monsoon2017 ..6 pic.twitter.com/MCpROK4jLo

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

..On the ground, about 2 km outside the old town of Patan, the water levels in an 11th century structure were rising. This remarkable ..7

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

..well, the Rani Ki Vav, was sited, designed, engineered and adorned exactly for rains such as this !! Town streets flooded and cars ..8 pic.twitter.com/sKD03C7sYp

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

..stalled. But the old channels & chambers of the Rani Ki Vav were proving the vision and sagacity of the celebrated stepwell’s creators ..9

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

..Designed as an inverted temple highlighting the sanctity of water, the Rani Ki Vav combines #water storage with exceptional artistry ..10 pic.twitter.com/CWxBh2cyW7

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

..We marvel at the foresight and knowledge of the Vav’s builders. To the north and north-west of the stepwell lay the zone in which this .11

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

..torrent of rain fell over 1/2 July, recharging the subterranean water storage system whose design origin is the 3rd millennium BC ..12 pic.twitter.com/wEWYyCRgnu

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017

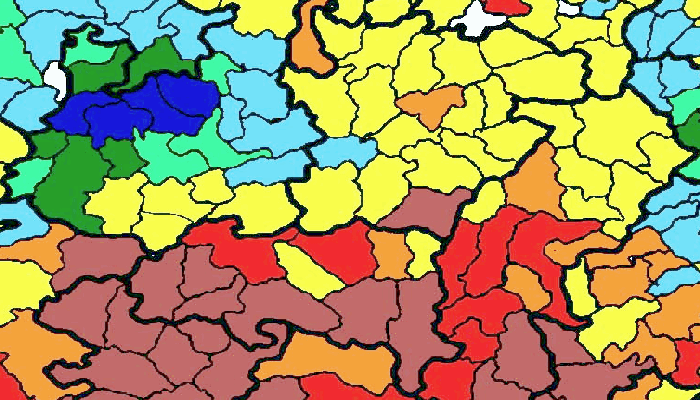

..This is the 4 hour 30 min sequence of intense #monsoon2017 rainfall in north #Gujarat and adjacent #Rajasthan – Rain for the Rani pic.twitter.com/zeuKb6SCZG

— Indiaclimate (@Indiaclimate) July 2, 2017