We find objectionable the report by ‘The Hindu’ daily newspaper accusing the India Meteorological Department of scientific shortcoming (‘IMD gets its August forecast wrong’, 1 September 2016). The report claims that the IMD in June 2016 had forecast that rains for August would be more than usual but that the recorded rain was less than usual.

This is nothing but cheap sensationalising by the newspaper of a non-issue. In so doing the ‘Hindu’, which is considered one of Bharat’s national newspapers, has attempted to tarnish the work of not only the India Meteorological Department, but also the work of the earth observation technical community which serve us in the several institutions and agencies of the Ministry of Earth Sciences.

There is no mainstream news media in the country – no daily newspapers, no magazine or periodical, no television channel, no internet website – which possesses the competence to assess the scientific quality and correctness of output of the government earth science agencies, and whose output is delivered to the public every day, several times a day. ‘The Hindu’ certainly does not and with this report exposes its ignorance about meteorology and climate science and observation.

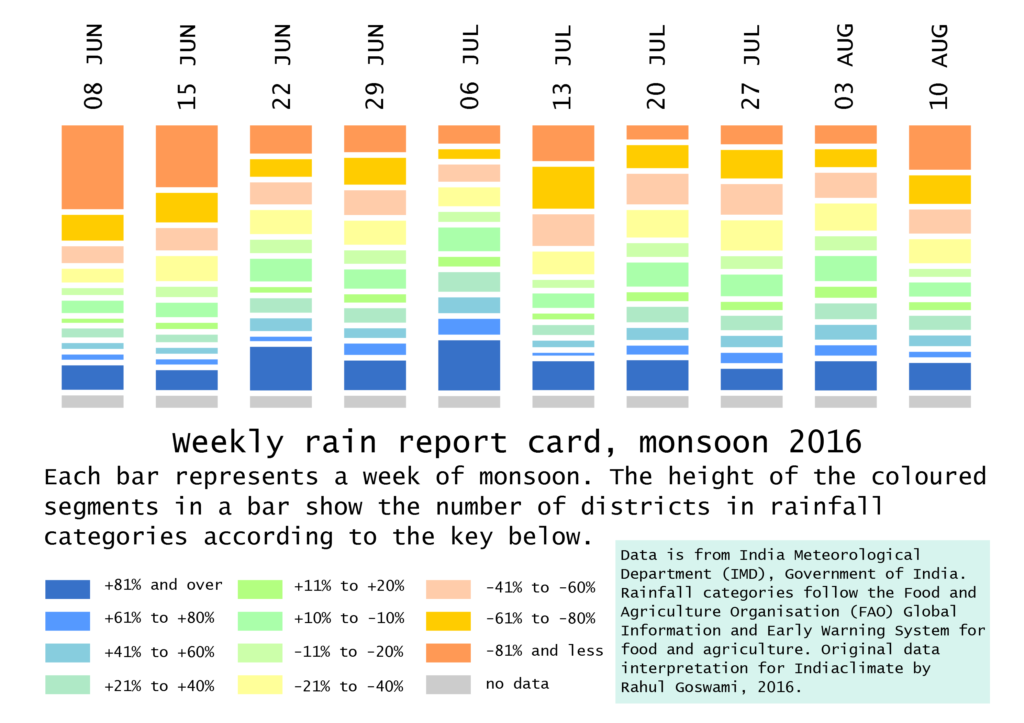

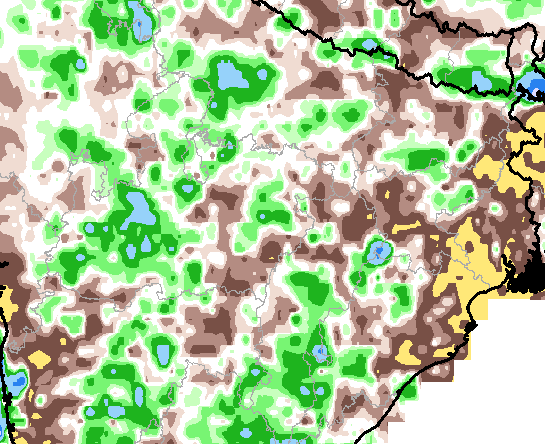

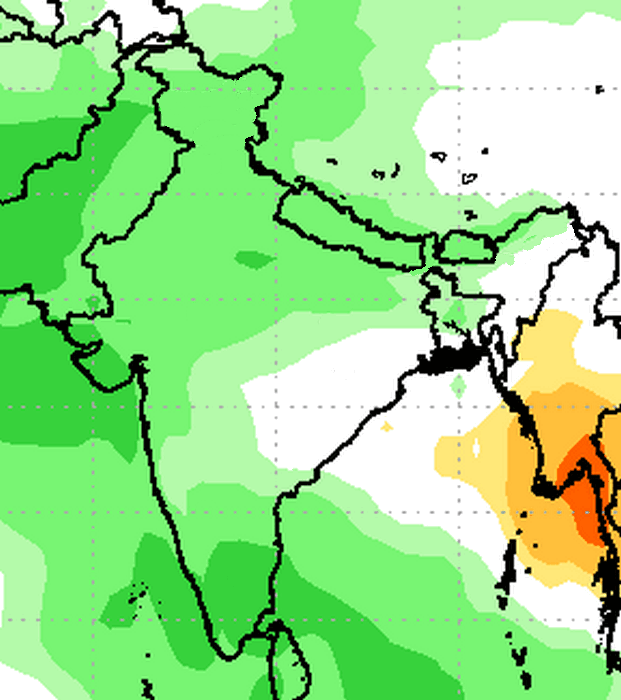

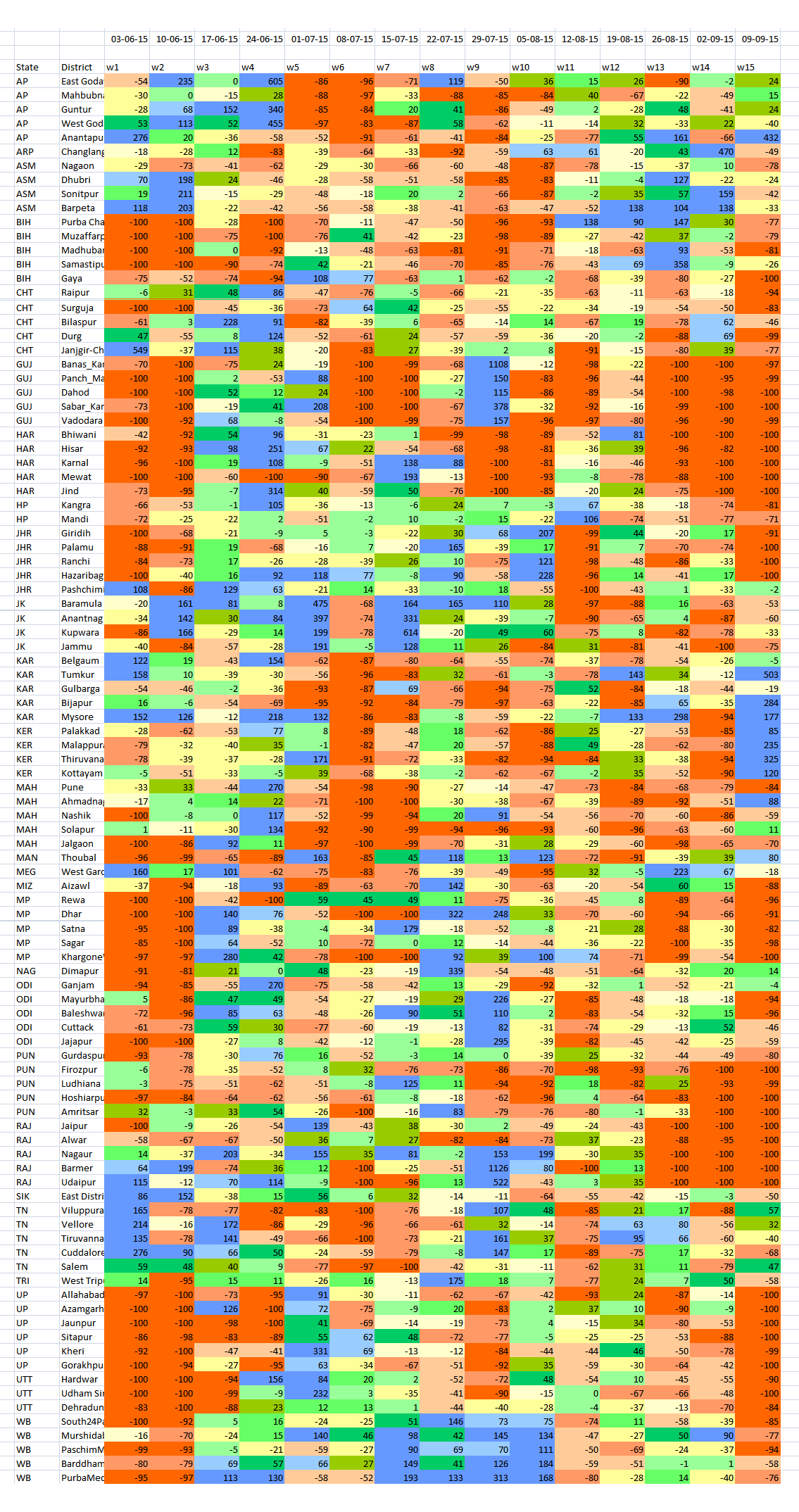

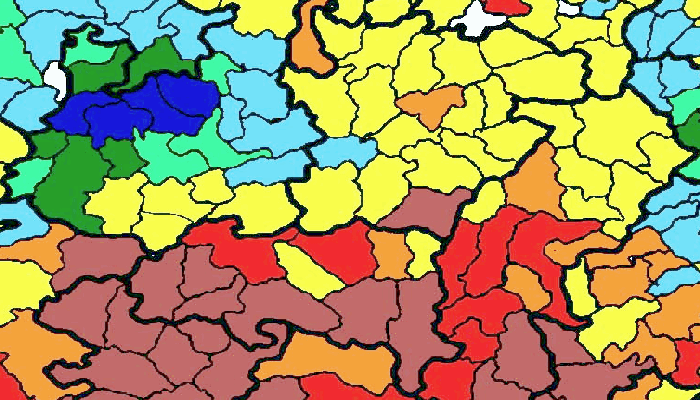

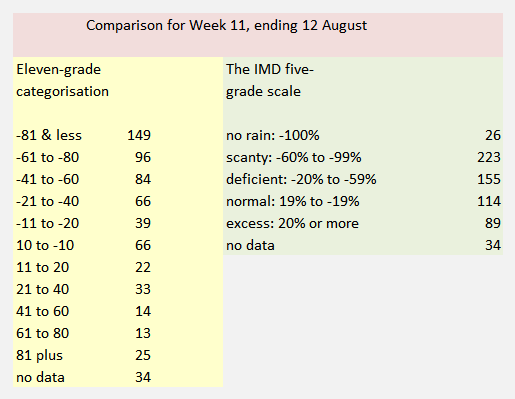

Concerning the newspaper’s claim, rainfall for the period 1 June to 31 August in the 36 meteorological sub-divisions of Bharat, as an area-weighted average, is -3% of the long period average and is therefore well within the boundaries set by both the first stage and second stage forecasts provided by the IMD. Of the 36 sub-divisions, for this period 24 sub-divisions have recorded normal rainfall, four have excess and eight (including the two island sub-divisions) have deficient rainfall. In what way is this an erring forecast?

The news report in the ‘Hindu’ states that the forecasting error it has found “suggests that the agency’s weather models are still not robust enough to capture changes in global climate that could affect” our monsoon. This is nonsense.

The earth observation agencies of the MoES – of which the IMD is a part – for the June to September monsoon forecast employs a group of six parameters that inform the forecast (together called an ensemble forecasting system). These are: north-east Pacific to north-west Atlantic sea surface temperature anomaly gradient, south-east equatorial Indian Ocean sea surface temperature, East Asia mean sea level pressure, central Pacific (El Nino region 3.4), sea surface temperature and tendency, north Atlantic mean sea level pressure and north-central Pacific 850mb wind gradient. In what way does this not look at global climate?

Moreover, the IMD and the agencies of the MoES (notably the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology) work closely regionally and internationally on climate science, weather prediction and monitoring. Not only is the IMD implementing for the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) a Regional Climate Centre for South Asia, the monsoon prediction and monitoring system relies on collaboration with: the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) of USA, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), the Met Office Hadley Centre for Climate Science and Services of UK, and with the national meteorological agencies of Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

And furthermore, it is because the Earth System Science Organisation agencies and institutes revise, review and upgrade forecasting models, computing wherewithal and methods continuously that we have in 2016 an experimental forecast (based on the Monsoon Mission coupled dynamical model).

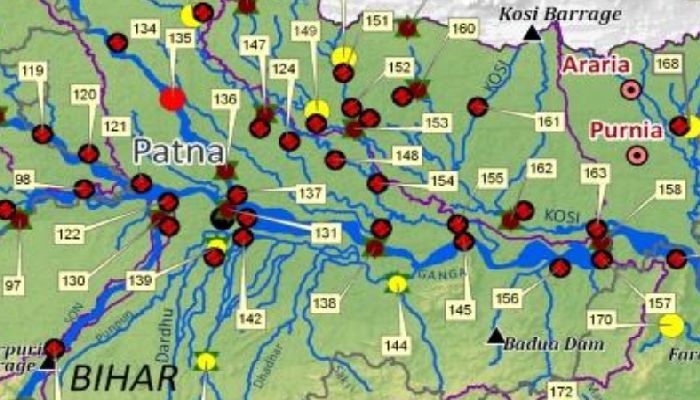

‘The Hindu’ newspaper has presented its own uninformed reading of differences in forecast averages to make an absurd claim against the IMD, neglecting entirely to mention the extremely valuable service provided, at the district and even at the block level, to Bharat’s kisans via daily sms on weather which will affect crops; neglecting the several excellent initiatives launched by the Department since 2015 on localising forecasts for towns and cities (in close coordination with the National Remote Sensing Centre of the Indian Space Research organisation, the Meteorological and Oceanographic Satellite Data Archival Centre of ISRO’s Space Applications Centre, and the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services.